At least 64 people in 22 states have contracted Salmonella after eating raw oysters, and 20 have been hospitalized, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced last week.

Infected people reported first getting sick on June 21 through November 28, the CDC said. Patients range in age from 10 to 76 years, with a median age of 52. Almost two-thirds of patients are male, and 85% are White.

The most affected states are Pennsylvania (10 cases), New York (7), New Jersey (6), Virginia (6), and Georgia (4).

Number of cases likely much higher

“The true number of sick people in this outbreak is likely much higher than the number reported, and the outbreak may not be limited to the states with known illnesses,” the CDC said. “This is because many people recover without medical care and are not tested for Salmonella. In addition, recent illnesses may not yet be reported as it usually takes 3 to 4 weeks to determine if a sick person is part of an outbreak.”

Official have not yet identified a common source of contaminated oysters. “Raw oysters can be contaminated with germs at any time of year,” the CDC advised. “Cook them before eating to reduce your risk of food poisoning. Hot sauce and lemon juice do not kill germs. You cannot tell if oysters have germs by looking at them.”

Cook them before eating to reduce your risk of food poisoning.

Raw oysters are a fairly frequent vehicle for the transmission of foodborne pathogens. Early this year, the CDC described two simultaneous norovirus outbreaks linked to eating raw oysters in California in late 2023 and early 2024 affecting about 400 Californians. A 2022 norovirus outbreak was traced to oysters harvested from Galveston Bay, Texas, while another that year was tied to raw oysters from British Columbia. Vibrio is another pathogen commonly tied to raw-oyster outbreaks.

A study of the leading bacterial causes of travelers’ diarrhea (TD) found wide regional variations in nonsusceptibility to the two classes of antibiotics used for treatment, an international team of researchers reported last week in JAMA Network Open.

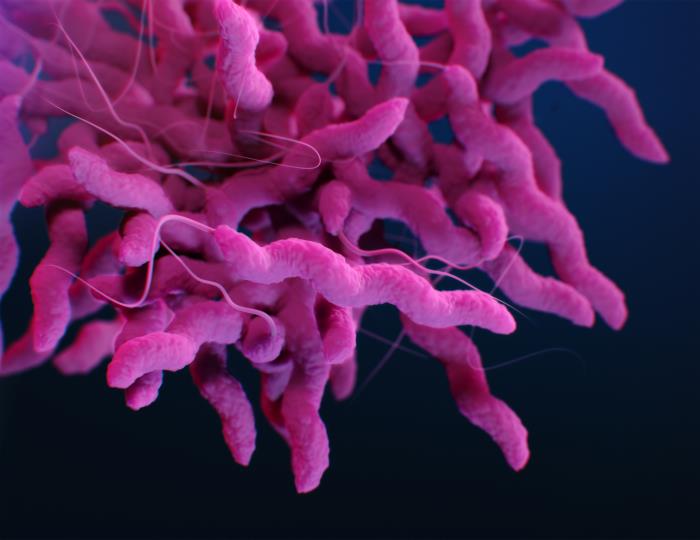

Using data from GeoSentinel, a worldwide network of tropical medicine centers located on six continents, the researchers conducted a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility data for four major pathogens causing TD, reported from April 14, 2015 to December 19, 2022. The main outcomes were demographics, clinical characteristics, and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of patients with culture-confirmed Campylobacter, Shigella, nontyphoidal Salmonella, and diarrheagenic Escherichia coli infections.

Current guidelines recommend fluoroquinolones or azithromycin (a macrolide antibiotic) for the management of moderate-to-severe acute TD. The study authors note that rates of resistance among isolates infecting international travelers have been limited to single-center studies.

Critical information for empiric treatment

Among pathogens isolated from 859 cases (median age, 30; 51% male) of TD from 103 countries, nonsusceptibility to fluoroquinolones was 75% for Campylobacter, 32% for nontyphoidal Salmonella, 22% for Shigella, and 18% for diarrheagenic E coli species. Among Campylobacter species, the highest proportion of nonsusceptibility to fluoroquinolones was observed in travelers to South Central Asia (88%), Southeast Asia (80%), and sub-Saharan Africa (60%).

Nonsusceptibility to macrolides was 12% for Campylobacter, 35% for Shigella, and 16% for Salmonella; 78% of Shigella isolates from South America and 24% of Campylobacter isolates from South Central Asia were nonsusceptible to macrolides. Twenty-six cases of Campylobacter infection were nonsusceptible to both fluoroquinolones and macrolides.

“Our findings have the potential to provide critical information for both the selection of standby empiric antibiotics for self-management of TD, and the empiric treatment of acute diarrhea in travelers, by travel medicine and primary care health care practitioners,” the authors wrote. “Our study findings also demonstrate the importance of surveillance of culture and susceptibility testing in TD in order to identify geographic patterns of resistance.”

Last week, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) announced that hunter-harvested deer in Dickson and Williamson counties had tested positive for chronic wasting disease (CWD), the first positive tests for both counties.

Dickson County is in the north-central part of Tennessee, roughly 35 miles west of Nashville. Williamson County is in the central part of the state, just south of Nashville. TWRA didn’t offer any details on the cases.

“Because these counties are not within or immediately adjacent to the current CWD Management Zone, there will be no changes to transportation or feeding regulations at this time,” it said in a news release. “However, hunters are now eligible for the Earn-a-Buck Program. Hunters can earn additional bucks by harvesting antlerless deer in Dickson and Williamson counties and submitting them for testing.”

Increased CWD sampling and monitoring

The agency said that it will increase CWD sampling and monitoring in Dickson and Williamson counties in response to the new cases. So far this hunting season, TWRA has submitted about 9,186 samples for testing.

Because these counties are not within or immediately adjacent to the current CWD Management Zone, there will be no changes to transportation or feeding regulations at this time.

CWD is a fatal neurodegenerative disease of cervids such as deer, elk, and moose. It spreads from animal to animal and through environmental contamination via infectious misfolded proteins called prions. There is no vaccine or treatment. While CWD isn’t known to infect people, health officials urge against eating the meat of infected or sick cervids and encourage using caution when handling carcasses.